(Dr Shujaat Ali Quadri)

“When we are dead, seek not our tomb in the earth, but find it in the hearts of men,” read the epithet at the tomb of Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi situated in Konya, Turkey. True to the words of the greatest mystic maverick, the people all over the world have been hunting him in the hospices of their hearts. Nowhere he has found as permanent a place as in India — the land of sages and sufis. In fact sufis like Rumi and Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi are stars on the firmament of India-Turkey relations. Since ancient history to the modern age, the bridge of sufism has kept both great countries of the world together. As Turkey is calibrating its policy towards India as part of its Asia Anew doctrine, India has too reciprocated emphasising on sufi or spiritual links between the two countries.

Exchange of translation

The exchange of sufi thoughts between India and Turkey may be traced to the Delhi Sultanate period in 13th century. However, when the Mughals ruled India, the sufi lodges in Ottoman cities became regular hosts of their Indian guests. Not only sufis, even diplomats travelled both the countries and carried scholarly texts back to their countries to translate and disseminate them among the nobles and the masses.

During this culturally and politically vibrant time, Hindu scriptures became a point of scholarly debate among Muslim Sufis. Several important scriptures and popular works were translated from Sanskrit to Persian and Arabic – the two languages of power and scholarship at that time. Most notable work that was translated was Hindu epic poem Mahabharata. The task was commissioned by none other than Emperor Akbar. His learned courtier Naqib Khan rendered the epochal work into Persian and named it Razmnama (Book of War). Other translations that followed were Rajatarangini and Ramayana. Similarly, poems and quatrains of classical sufis like Rumi were translated into Sanskrit, and later Hindi.

One of the modern illustrious examples of Rumi’s poetry being translated into Hindi is Nishabd Nupur, a translation of 100 ghazals of Rumi by a Delhi University professor, Dr Balram Shukla.

In fact one of the longest poems of Rumi, The Faithful are One Soul, is believed to have been inspired by Upanishads as it is very close to the meaning contained in the great Sanskrit texts.

Sufi-Vedantic interactions gave rise to the concept of Waḥdat al-Wujud (Unity of Being). It has since been sine qua non of sufi traditions in South Asia.

Sufi takiya (lodge)

When these South Asian sufis travelled to the Ottoman Empire, they established their own schools there and these schools or sufi centres, called tekke or takiya, have been popular till date. They were prominently established in modern Syria’s Aleppo, modern Iraq’s Baghdad, modern Turkey’s Istanbul and Edirne, even modern Bulgaria’s Sofia and modern Kosovo’s Prizren.

One of the most well-known sufi takiya in Istanbul is the Horhor Tekke in Üsküdar, which has recently been renovated. According to archival documents, some Mughal and other Indian diplomatic missions acknowledged the importance of the Horhor Tekke. Imam Muhammed Serdar was a member of the diplomatic delegation of Tipu Sultan, ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India in the 18th century, and had stayed at this tekke where he was buried after he died.

Sheikh Sirhindi or Imam Rabbani

In Turkey, the most famous and omnipresent Indian mystic figure is 16th-century Indian Sufi, Ahmad al-Faruq al-Sirhindi, also known as Imam Rabbani. The collection of his letters known as Mektubat-e Rabbani enjoys the status of a sufi magnum opus and this book is found in every library and sufi takiya in Turkey.

Little details are available about Sheikh Sirhindi’s time period spent in Turkey or his direct interactions with Turkish travellers, the papers from the Ottoman archives compile together stray strands from 19th century onwards.

“Baghdad-based famous Sufi Khalid-i Shahrazuri met the Indian traveller and spiritual seeker Mirza Rahimullah Azimabadi, who told him about Imam Rabbani and his disciple Abdullah Dihlevi. Shahrazuri took no time in visiting Delhi in 1809 and attended the circles of Imam Rabbani’s disciples, especially of Dihlevi. He spent more than a year learning the teachings of Imam Rabbani. Shahrazuri returned to Baghdad in 1813. As per the Ottoman archives, Dihlevi also sent his disciples to Anatolia to establish takiyas,” says one paper. Similarly, there are anecdotes about Sirhindi’s later day family members like Halil Efendi and Sheikh Masumi were granted state hospitality by Ottoman sultans.

Rumi, the Indian ‘connection’

Like his poetry and philosophy, Jalaluddin Rumi has a mystic connection with India. Shamsuddin of Tabrez to whom he had dedicated his collection of Ghazaliat as Diwan e Shams e Tabrezi is believed to have Indian ancestry. According to Orientalist H.A. Rose, he was probably of Indian origin who identified himself with Shamsuddin Tapriz of Multan, a great contemporary saint and who got the sobriquet of Tap-riz or ‘heat-pouring’ because he brought the sun closer to that spot. Dr Rasih Guven too supports this view and states that his father Khawand Alauddin was an Indian and a new convert to Islam and his name was Govind, a Sanskrit word.

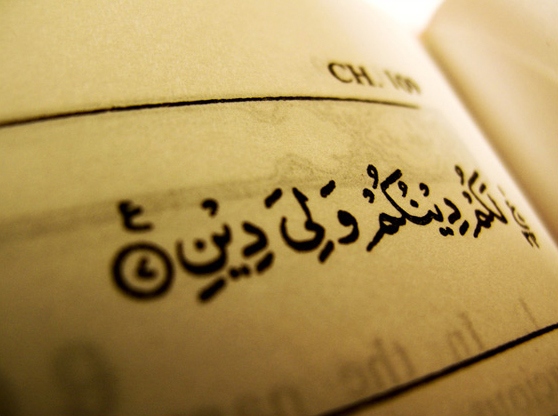

Although Rumi’s works are literary works of a Muslim jurist and mystic, written in the Persian language, they crossed the barriers of language, religion and culture to reach different peoples belonging to different civilisations and cultures.

The first printing of Masnavi (the Persian version) was in Cairo in 1835. In India, however, Rumi reached much earlier. Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, the great guide of the Chishti sufi order, wrote a commentary on Rumi’s Masnavi in the 14th century.

Rumi’s greatest influence on Indian culture in the modern era has been poet and philosopher Muhammad Iqbal, who considered Rumi his spiritual guide and “the prince of the caravan of love.”

The poets and saints of Bhakti tradition like their sufi counterparts too always have been attracted to the message of Rumi and even today Rumi continues to inspire many including neo-religious movements like Radhaswami. His Persian verses when sung with Dhrupad have manifested into a unique confluence of words and rhythm.

Dr Shukla puts it in the introduction of Nishabd Nupur, “Rumi advocates oneness of existence which leads to the cessation of hatred, and hence makes love inevitable.” This message has never been as relevant as it is today. It will not only bind countries together, it will weave people into one entity, one wajud.

(The Author is director of Indo Islamic Heritage Foundation)