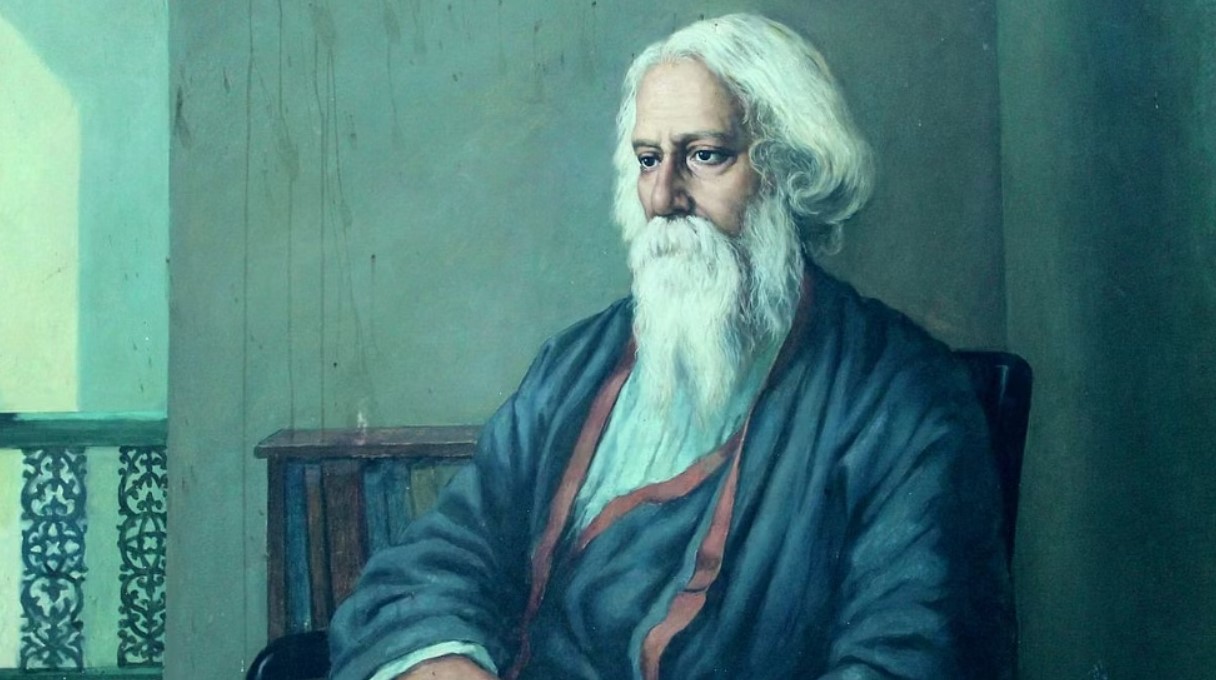

Bengali polymath and Asia’s first Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore binds India to countries in West Asia through literary fabric. Tagore, whose artistic and literary pursuits turned him into a ‘universal man’, serves as the most enduring diplomat for his country.

The international humanism in Tagore’s writings is celebrated throughout the globe. The Indian poet and philosopher was a proponent of a resurgent Asia and wished to see the region rising as the pivot against the colonial West.

In his tribute to modern Turkish leader Kemal Ataturk, who overthrew the Caliphate to found a modern republic, Tagore said: “Kemal set us an example of a resurgent Asia.” Tagore himself had travelled to meet Ataturk in 1922 to congratulate for the feat.

Inspired by Tagore, a new generation of West Asian leaders emerged who looked up to Japan for technological advancement and to India for their spiritual and intellectual pursuits. They were labelled as pan-Asianists.

Tagore and Turks

Turks in the 1920’s were a jilted lot. They were disillusioned by redundant ideas carried through by centuries old Ottoman Caliphate. In addition, the occupation of their territories after World War I had left them in complete disarray. Tagore inspired the generation of such

Turks and offered them intellectual resistance to the West and a confidence to enter a new century.

Tagore’s speeches and writings began to appear in various Turkish journals and newspapers after 1915. Ottoman journals and early republican journals such as Sebilü’r-Reşad, Anadolu Mecmuası, Idjtihad, Hayat and Milli Mecmua were regularly following Tagore’s works and had started translating some of his works into Turkish.

The Home and the World was the first novel of Tagore translated into Turkish. In later years, almost all of his works were translated into the Turkish language. The Gardener, Fruit Gathering, The Crescent Moon, Gitanjali, The Post Office, The Fugitive, Stray Birds, The Home and the World, Chitra, Lover’s Gift, The Religion of the Poet, Gitanjali and The Cycle of Spring have been translated and widely publicised for Turkish readers since then.

All these works are regularly showcased in literary exhibitions in Turkey and can be found in bookstores in all major cities even today.

According to literary commentators, what attracted Turks most was that Tagore in his writings gave vent to a stream of new and almost religion-neutral ideas. “Tagore was opposed to European nationalism, which was conceived around narrow ethnic, linguistic and even religious biases,” wrote a commentator in Daily Sabah newspaper. Tagore set a tone for multi-ethnic, multilingual and racism-free world and Turks took to these thoughts enthusiastically.

Glowing tributes were paid to Tagore in Turkish journals. He was almost like “Guru Dev” to intellectual Turks as he was to Mahatma Gandhi. A journal called Dergah wrote on August 5, 1920, “The biggest guard of India’s independence sings the song of freedom to Indian children in the peace march in the forests of the Gulf of Bengal; he, walking barefoot, sang the songs of freedom and songs of free birds.”

Turkish writer Safia Sami found Tagore at par with Tolstoy and Dostoevsky in his appeal to Turks. “Tagore successfully mixes sensitivity of the East and aesthetic perfection of the West. However his poetry appears in a local context, it doesn’t give the feeling of foreignness,” she wrote in the journal Milli Mecmuasi in its January 1927 issue.

With his message of fraternity and peace, Safia says, Tagore became a Murshid (spiritual guide) among all nations, a role for which he established the Shanti Niketan, the fort of peace (Sulh Kilasi).

One Ottoman bureaucrat and literary figure Süleyman Nazif wrote an introduction of Tagore in the Inci journal in which he called Tagore equal to Omar Khayyam.

Such was Tagore’s fascination for Turks that Tagore’s iconic poetic collection Gitanjali was translated in Turkish many times, once by none other than Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit himself in 1941.

Paying its tribute to the literary giant, the Turkish government in 2003 named a street in capital Ankara as Rabindranath Tagore Street and his poems and plays are regularly recited and staged at various Turkish platforms.

Indian mission organises Tagore events on regular intervals, with invitation to some Turkish expert on the laureate to illustrate resonance of his thoughts in modern times. The Turkish mission in New Delhi reciprocates with similar events and also sometimes organises exhibitions of Tagore’s paintings.

Poet in Persia

Persia, now Iran, was a natural haunt of poet Tagore. When he was on the peak of his glory, he received invitations from several heads of states. He obliged selected few and travelled to those lands despite his dwindling health.

In his zeal to modernise Iran, then ruler Reza Shah Pehlavi decided to revive ancient ties to India and invited Tagore to tour Persia and suggest ways to reform society and thoughts. Tagore took Pratima Devi, his daughter-in-law, and Amiya Chakravarty, his literary secretary, and flew to Iran, in 1932, 20 years after he received the Nobel Prize.

In Iran, he travelled through all historical places that had connection with India. Iranians were charmed with his grace and depth of his thoughts. Wherever he went he was thronged by admirers.

In fact, the reception held for Tagore at the shrine of Sheikh Sa’adi (a popular Persian poet) got such a huge response that the Iranian authorities had to deploy the army to control the people who had come to see the famous poet from Bengal.

The reason behind Iranians’ enthusiasm to greet Tagore was that the Tagore family, according to one account, was called Pīr-‘Alī Brahmins, or the followers of Imam Ali.

The ecumenical teachings of the Persian Sufi tradition and the rich heritage of Persian poets such as Aṭṭar, Rumi, Sa‘di, Shabistari, Ḥafiẓ, Jami and others were well known in the Tagore family.

Tagore was eager to pay tribute at the tomb of Hafiz in Shiraz. When he reached there, he delved into a deep meditation. The steward in charge of the tomb complex handed Tagore a large Ḥafiẓ’s Divan or the book of Hafiz’s poetry.

He suggested Tagore take an augury from Ḥafiẓ’s poems by reading a poem from opening the book to a random page (an ancient Iranian tradition).

When Tagore opened the Divan, the immortal Ḥafiẓ, known to Iranians as ‘the voice of the wise, offered these verses to the Bengali poet’s rumination over the evils of religious puritanism:

‘Will there ever be a time when the taverns’ doors open again? Will there ever be a time when the deeply entangled affairs loosen up again? …’

… and Hafez promised that victory would be attained.

During his Persian sojourn, Tagore met a number of intellectuals and religious scholars who inquired about his thoughts on religion, society and modern age. In one such interaction, his articulation on religious guidance left an indelible mark on the minds of Iranians.

One evening, Tagore was visited by local Islamic scholars who asked him how one could decide the right path to follow among the many religions of the world.

Tagore gave his answer through a simple story, “Suppose all the windows of a room are closed and a person is then asked how he/she can get some light, someone may give the answer as striking flintstones. Another may say by lighting an oil lamp, yet another by a wax candle, and someone else by switching on an electric light!”

In order to strengthen ties between India and Iran, during his visit, Tagore requested the Shah of Iran to appoint a Professor to teach Persian literature in Shanti Niketan.

Tagore used to celebrate the festival of Navroz, the Persian New Year, with fervor at his ashram every year.

In 1961, the centennial year in honour of Tagore’s 100th birthday, the celebrations were organised both in Iran and India. Iranian ambassador to India Moshfeq Kazemi went to Calcutta to take part in various events marking the birthday of the bard. A prominent school in Tehran Shirin High School was named Tagore High School in 1962.

Even after the Islamic Revolution in 1979 that replaced the monarchy with a rule of religious clerics, Tagore retained his place in Iranian libraries and public celebrations. In 2011, then Lok Sabha Speaker Meira Kumar visited Iran and unveiled the Persian version of Tagore’s poem Paroshye Janmodine, meaning A Birthday in Persia inscribed as a plaque in Iranian Parliament.

Bard in Baghdad

After his long and successful sojourn in Iran, Tagore crossed borders into Iraq and paid a visit to King Faisal of Iraq in Baghdad.

The Iraqi monarch held a state banquet for Tagore, that the poet later remembered in his diary for its “unassuming hospitality” and the “artless gravitas” of King Faisal. In the speech he gave on the day, Tagore also thanked the people of Iraq for welcoming a poet despite the “utilitarian urgency of this machine-driven age”.

Tagore’s books – in all their genres like poems, novels, dramas – have been prominently displayed in Baghdad bookstores since his visit to Iraq.

Cairo Connection

Tagore promoted Asian unity and connected with intellectuals who had the same goal as he did: to bring culture to the masses. In his quest, he visited Egypt in 1926-1927 and the then King of Egypt presented him with a set of books in Arabic. During the visit, Tagore also formed a very strong relationship with noted Egyptian poet Ahmad Shawki, who was known as Prince of Arab Poets.

Tagore and Shawki kept communicating and exchanging views for a long time till Shawki’s death in 1932. Shawki’s villa has now been turned into a museum. It also hosts some of the articles sent to Shawki by Tagore

The Maulana Azad Centre for Indian Culture in Cairo regularly organises recitation of Tagore’s poems, rendering of Rabindra Sangeet and dance.

Gibran & Tagore

Kahlil Gibran is undoubtedly the most ubiquitous literary name from the Arab world. His magnum opus Prophet is one the of largest selling books of poetry, establishing, like Tagore, as the Arabs’ best cultural diplomat.

Last year in June, the Indian embassy in Beirut organised a painting exhibition called “Gibran hosts Tagore” that commemorated works of both Gibran and Tagore. It was the first time that Tagore was celebrated in Lebanon on such a scale, but the Indian mission said that Tagore would continue to resonate in Lebanon’s literary circles.

Both Gibran and Tagore enjoyed a friendship that was based on understanding each other’s words without having to talk directly. The two bards met many times between 1916 to 1921.

Both of them were from the “East” and yet they chose to address their Western audience in their own language, English. Both of them were from the countries under foreign occupation at that time; Lebanon under Ottoman rule and India under British rule. Both of them had seen the suffering and pain of their people, especially due to famines, in Lebanon and in Bengal from where Tagore came. Yet they decided to give their people a message of hope, peace, freedom and enlightenment.