HUSSAIN RANDATHANI

The popular culture of every region is determined and moulded by geography, climate and mode of life of the people. The culture is enthusiastically preserved by peasant societies rather than the urban people whose cultural obligations are mostly superficial. The beliefs, rituals and rites always had a place in the evolution of folk culture and whenever an alien faith comes into contact with a community, there occur interactions between the faith and the existing culture of the community producing a new cultural orientation. This was true of the Muslim Mappilas of Malabar where the spread of Islam produced a distinct f Islamic regional culture termed as the Mappila culture. Here the proliferation of indigenous elements, the Islamic doctrines, sufi and other religious orders and fraternities created favourable atmosphere for mixing together of the officially prescribed rules of religon with folk features either barely tolerated by the leadership or even proscribed by them. Many of the exogenous features of indigenous culture of the region have survived within an Islamic frame work without being clearly differentiated from official Islam or being recognised as elements of culture of the religions.

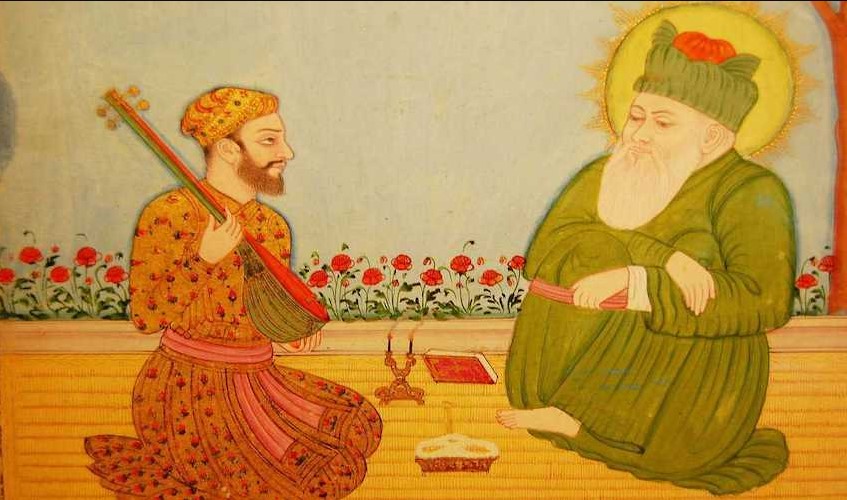

Despite the above factors, the spread of Islam in Malabar was made in conformity with the spirit of faith, without any imperialistic designs. The mystics and merchants who acted as the missionaries of Islam followed a policy of sulh i kul (peace with all), respected the ancient customs and obeyed the rulers. The rulers, who were the up keepers of the Hindu religion, on the other hand gave official sanction and facility for Islamic missionary activities. Shaikh Zainuddin reports in the sixteenth century that,” these rulers had respect and regard for the Muslims, because, the increase in number of cities was due to them. Hence the rulers enable the Muslims in the observation of their Friday prayers and celebrations of Id. They fix the allowances ofqazis and muaddins and entrust them with the duty of carrying the laws of the shariath 1. The deep doctrinal differences between Hinduism and Islam in no way affected the mutual co-existence and cultural assimilations. While manifestations of folk religion often contradicted official Muslim monotheism, the Mappilas remained unaware of such contradictions and the religious authorities in most cases were inclined to tolerate the regional customs and traditions.

Bulk of the Mappila population belonged to the converts from among Hindu low castes and these neo converts, to a great extent maintained their caste rules even after professing the new faith. Mass conversions made it impossible a systematised religious instruction among the new converts and this naturally gave the folk traditions a place in the Islamic core of Mappila society. At the same time the Hindu upper castes not only found any objection in the conversion of the low caste, but also provided warm reception to the neo converts.2. The converts on the other hand followed the caste traditions in respecting their old masters. The most important Mappila folk culture in which the Hindu-Muslim rapprochement becomes more evident is the ceremonies connected with the saints and mystics. Veneration of saints and holy people whose tombs are places of pilgrimage and great gatherings especially on their birth days and anniversaries of their death, has been a part of popular Islam. A living or dead saint plays an important role in the social and cultural life of rural Muslims, that his khanqah or mausoleum becomes a centre of hope and refuge. For sufficient rain, to get rid of locusts and for fine harvests the people, or to get profits in the business the people, despite their religious differences, gave offerings in the name of the saints and made prayers at their mausoleum (dargah)3. According to the belief the saints while alive were endowed with barakah, a beneficent super natural potential or virtue and this force emanates from their tombs, so that a visit to a saint’s shrine can benefit the supplicant. In southern Malabar it is a common practice among the Hindu peasant class visiting the dargah of Sayyid Alawi Tangal of Mambram in order to fulfill their wishes and to get blessings for their ceremonies. All classes of people especially the rural people respected the tangal and he became the nucleus of peasant struggles in 19th century. His manager Konthu Nair, a Hindu served him throughout his life as his confident karyastan4. Kozhikkaliyattam, a Hindu peasant festival at Kaliayatta Mukku near Tirurangadi is said to have started with the blessings of Sayyid Alawi. The folk song on Kaliyattakkavilamma bears testimony for this :

On 15th Edavam

A good festival (Kaliyatiam)

Was fixed on Friday a good day.

By Sayyid Alawi Tangal

He launched the festival

And it continues as

Blessed by him.5

The Mappila folk festival called nerchas or urs had close resemblance with Hindu festivals in a number of aspects. The differences mainly exist in the chanting and prayers, that both the communities use the prayers of their own respective faiths. The social and economic interests of the festivals and nerchas are same with the only exception that the distribution of food to the poor has been found a especial feature of the nerchas. For the people of the locality the festival or nercha is a centre of business activities of house-hold articles and every house in the area is involved in the festival irrespective of religious differences.

The Kondotty nercha held in the name of Mohammad Shah (d. 1766-67) is a platform of harmony among different religious groups. Mohammad Shah was very friendly with the Hindu devotees (swamis) and his hospice was built near their residence called ‘Swami Mut.’ The swamis actively participated in the nerchas and traditionally their descendants offer a silver flag to his dargah during the festival. Goldsmiths and untouchables of the area were very close to the tangal and during the festivals two processions (pettivaravu) are led by the goldsmiths and Harijans respectively.6

Shaikh Mamukkoya (d. 1562) in whose name the Appa Vanibham nercha (the Bread festival) is held, is respected by all communities. During the festival all the communities offer bread at his dargah. They put coins in the offering box in order to fulfill their wishes. The same attitude is found in all the Mappila festivals which became a bond of communal harmony in the respective localities. The Muslim mystics and sayyids under whose name these festivals are held had set the tradition of peaceful coexistence among the different religious groups.

The Hindu Muslim cultural confluence is also evident in the Mappila art and architecture. The Muslims followed the indigenous art forms with slight variations. Mappila art called kolkali is the Muslim version of the indigenous art known as kolattam or koladipattu. In ancient times it was an art of women folk. The origin of the art is connected with Vishwakarmar, (those who carve out Gods), who made sticks measuring twenty one fingers from sami tree (chamata) and gave them to Lord Krishna. He gave the sticks to the gopikas (ladies who pasture the cattle) who started to play with the sticks.7 Later the low castes made it their own art and used to play during the festival seasons. Mappilas islamicised this art by changing the Hindu devotional songs to Islamic. Mappilas start their kolkali with pryers to Allah, Prophet Mohammed and sufi saints.

The Kerala martial art called kalari payattu was directly adopted and practiced as their own by Mappilas. Kalari was originally intented to foster martial spirit among the Nayars and keep them fit to fight in battles. The kalari schools were generally attached to Bhagavathi temples and it was presided over by asans (master) or gurukkal. Later Mappila Muslims also adopted this martial art and started it in Mappila localities. The northern ballads refer to Muslims trained in kalarippayattu. Tacholi Othenan, the hero of northern ballads himself had made obeisance before Kunhali Marakkar, the Mappila commander of the zamorins, and offered presents to him before establishing his kalari.8 Muslims often received their training in the Hindu institutions called Chekor Kalaris.9 The paricha kali is an adaptation of kalaripayaitu and the Mappilas had developed their own tradition in this art which is known as parichamuttu. The participants wear white shirts and green cap and sing Mappila songs after praying to Allah, Prophet Mohammad and saints. The oppana dance of Mappilas resembles the kaikottikkali and vattappattu practiced by Hindu women, though it is more connected with its Arabian varieties. The Muslims scholars take the derivation of the term oppana from the Arabic word hafna which means, to put the palms together. But the fact remains that the word oppana was prevalent in Malabar since the ancient times and the processions in certain temples are known as oppana vekkal10. Now oppana developed as a national art and it is played during all the national festivals.

The Mappila dialect called Arabic-Malayalam is also a product of Hindu Muslims synthesis. It was created by giving Arabic script to Malaylam letters and was further enriched by adding a number of words from the folk dialect and other languages. We have abundant collections of Mappila folk songs called Map-pilappattu and their origin is mainly from the indigenous culture with modes or ishals taking from the old Dravidian styles. For example, the mode tongal resembled with the style of ‘maveli naduvanidum kalam, adi antham resembles with ‘omanakkuttan Govindan’ and pukainar is the Mappila version of Hindu ‘vanchipttu’ (boat song). The Indian languages like Sanskrit, Hindustani, Kannada and Tamil had vastly contributed to Mappila folk songs.11 Influence of Malayalam poets like Cherusseri, Ezhuttachan and Kunchan Nambiar is seen in the Mappila songs written by Moyin Kutty Vaidyar, the Mappila poet of nineteenth century. Suranat Kunchan Pillai relates the mixing of different languages in the Mappila songs with that of Unnayi Varier.l2The folk song malapattu is the Mappila version of Hindu kirtans and the pakshippattu had a Keralite version of called kilippattu in Malaylam. The kuppipattu and kurathippattu contain the traditions connected with the local culture.

The Mappila folk tales had very much to say about communal harmony. The tales connected with Kunhayan Musliyar and Mangattachan vividly describe the communal harmony existed in the zamorin’s kingdom. Kunhanyan Musliyar. a Muslim scholar of the nineteenth century is known for his jokes in Mappila circles. Mangattachan, the chieftain of zamorin was his close friend. Once the Musliyar and the Achan were in a journey. On the way the Achan respected a tulasi plant, took some of its leaves and put it on the ears. To make fun of him, the Musliyar took few leaves and after rubbing it in his private parts threw it away. The Achan saw this and waited for an opportunity to answer his friend and continued the journey. When they reached near a kodithuwa plant (tragia involuera) the Musliyar after respecting it took some leaves and put them in his pocket. The Achan thought that it was a revered plant for Muslims and without wasting the opportunity took some leaves, rubbed in the private parts and threw them away. The Achan suffering from acute itching, confessed his failure before Musliyar.13

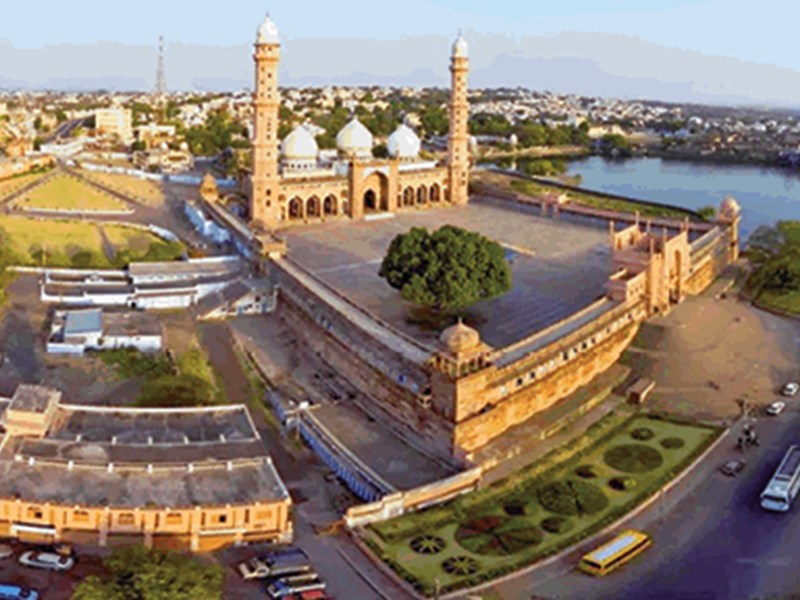

“The unique Mappila mosque architecture” writes R.E. Miller ” not only reflects the Mappila community’s integration in Kerala culture but also its isolation from Indian Islam. Instead of following the Mughal pattern, Mappila mosque observe the indigenous Jain style of architecture.”14 The mosques resembles Hindu temples in all respects except the interior where the prayer nitch (mihrab) and pulpit are arranged as in the Muslims fashion. The traditions assert that “the similarity was due to the fact that friendly kings had made over temples and their properties to the early Muslims converts and the temples were converted in to mosques with the least modifications to suit Muslim requirements.15 The fact remains that early mosques were built purely by Hindu carpenters and masons who followed Hindu style and in the earlier mosques even the trisul, the Hindu symbol was carved in front of the gable.16 There are also instances of temples converting to mosques when the inhabitants of the place were converted to Islam en masse. There was also the practice of providing grants by the zamorins to maintain mosques. The inscription of one such land grant is found in the Muchunti mosque at Calicut with details of land given by zamorin to that mosque.17 Temples and mosques were erected side by side maintaining harmony between Muslims and Hindus. In the mosque called Sheikhinte Palli, constructed near by Chalat Shasta temple no animal sacrifice is made during Bakrid as a respect to the temple 18

The cultural harmony between the two communities is evident in the Mappila social life. In the sphere of social customs and practices Mappilas had borrowed many things from Hindus while religious practices and theology were remarkably unaffected. Miller has put the matrilineal kinship called marumak-katayam as the most illustrious example of Mappila social adaptation from Hinduism.19 But it is found that the system was adopted not only by Mappila Muslims of Malabar but also by all the Muslims communities generated by Arab sailors. The system also existed on the coast of south Arabia particularly in Yeman from where the Arab sailors used to visit the Malabar coast. The system was particularly suited to the peculiar mode of life of Arab sailors who made full use of this indigenous institution.

In the customs and ceremonies ranging from dress habits to marriage practices including such customs as tying the tali (necklace that symbolizes marriage) and paying dowry to the bride groom, the Mappilas followed indigenous style. In food and dress also they follow the local styles with slight variations. For example, the Mappilas wore their lungi (mundu) with its outer edge to the left while the Hindus put the edge to the right. In the field, of magic and witchcraft the peasant Mappilas often followed Hindu practices, though their religion strictly discourage them. They approach the Hindu divines to save themselves from sorcery and evils. Placing a hideous figure made of wood or straw in front of a new building or a bogey in the model of women made of straw in the vegetable fields to avert veil eye are few examples. Belief in the odi cult, omens and the local devils are common among the Mappila folk.

Thus, a socio-cultural analysis of Mappila society would reveal the friendship and harmony maintained by it in its origin and development. The local Hindu rulers who were cordially related to the Mulsim mystics and missionaries. The rajas took all the pains to protect the community because the economic prosperity of rajas was due to them. The mutual dependency had thus helped to a great extent, in bringing harmonious relationship between the two communities. The attitude of rajas would, naturally influence the Hindu groups and they also followed a policy of reconciliation with their Mappila brothers. That is why the cultural symbiosis and harmony is more obvious among the Mappila Muslims than among the other Muslims groups.

Notes:

- Shaikh Zainuddin, Tuhfat ul Mujhidin, Tr. Husayn Nainar. Madras, 1945, p. 51.

- See Kumaranasan, Asande Padya Krithikal, Study, Nitya Chaitanya. Yathi.. Kottayam, 1990, p. 509.

- Trimingham, Sufi orders in Islam, Oxford, 1986, p. 3 1.

- C.N. Ahmad Maulvi, Mahuthaya Mappila Sahitya Parambaryam, published by the Authors, 1978, p. 178

- Salim Idid, ‘Katha Parayunna Mambram’ Chandrika Daily. 27.4.91. p. 3

6 Dr. J.J Pallath (ed.) Samudaya Mythri Mathaghoshangalil. Sanskriti publications, Kannur, 1993,

- S. Mohan Chandran. Kolkalipputtukal, Oru Padanam. Published by the Author, 1989, p.47

- PK. Muhammad Kunhi, Muslimingalum Kerala Samskaravum. Thrissur. 1982, p. 398.

- Anantha Krishna Ayyar, The Anthropology of Syrian Christans, Ernakulam, 1926, p. 54, There is an opinion that kalari was introduced to Malabar from Karnataka region where it was patronised by the nawabs. The nawabs on the other hand brought the tradition from Khurasan in Persia, see P.K. Mohammad Kunhi, op cit, p. 309

- Balakrishanan Vallikkunnu, ‘Oppana Yenna Kalarupam’ Mappila Kalarupam ed., OM Karuvarkundu, Manjeri, 1995, pp. 34-35.

- Dr. M.N., Karasseri, ‘Mappilappattu, Malabar, Prof M.G.S. Narayanan ed., 1994. p. 607.

12.Suranat Kunhan Pillai, ‘Mappilapattukalku Moyinkutty Vaidyarude Samhhavna” Chandrika Republic Edition 1970.

- Pakkar Pannur, Kunhayan Musliyarum Mangattachanum, Tirurangadi, 1996 p. 50

14.R.E. Miller, Mappila Muslims of Kerala, Madras, 1976, p. 250.

- AP Ibrahim Kunhu, Mappila Muslims of Kerala, Trivandrum, 1989, p 189.

16.William Logan, Malabar Manual, Vol. I, Madras, 1951, pp.186-187

17.For Details of the inscription see, M.G.S. Narayanan, Cultural Symbiosis in Kerala, Kerala Historical Society, Trivanduram, 1972, pp. 38-42

18 P.K. Muhammad Kunhi, op. cit., p. 85 19. Miller, op. cit., p. 252.